Part One: Athens

“When in Athens, live as an Athenian.” Dr. Constantine

We sit side by side waiting for the flight from Lisbon to Athens. The good man, Dr. Constantine, big-boned like a stevedore, eyes me. “What happened to your face.”

As I explains, he nods sympathetically. “It will heal.”

“What about my pride?”

He laughs. “That is another matter.”

When our flight is called, we say goodbye; I tuck his advice into my pocket. Advice that often comes to mind over the next week as Sailor Boy and I walk through the seat of antiquity, a crazy, mad city, broiling with heat in September, crawling with tourists, merchants hawking cheap goods, and above it all a marble apparition, the Acropolis.

The first morning we brave the crowds, the motorcycles, and the humidity to walk through the Sunday Flea Market, soon retreating back to our hotel room in the Plaka to cool off. While the tourists seem oblivious to the mood of the hawkers, I observe tension on the faces of the Greeks, an aggressiveness in their posture as we pass on the sidewalks.

I take a moment with the young woman at the front desk at our hotel. “What can you tell me about life in Athens?” I ask. Two hours later, she is still passionately trying to explain the effects of the 2010 Crisis.

“When the Greek government, burdened by debt, collapsed, one million people were suddenly unemployed. The middle class including professionals like doctors and lawyers and freelancers lost their jobs. Small shop owners shut down. The EU and IMF stepped in to save the country. Greece lost her sovereignty. Now the people are intensely divided and mired in the complexity of a political situation that swings from fascism to socialism to nationalism. Macron is coming to visit and what will happen? Nothing. Our politicians do nothing. They tax us for everything and nothing changes.”

She continues, “The sites are a historical way of knowing Greece, but to know the people listen to the music, eat the traditional food, and visit the shipyards. We have a passion for life, too much passion. Sometimes we feel more than we think, but,” she shrugs, “that is who we are.”

At sunset, we catch a cab to Café Avissinia in the Monastraki and climb up three flights onto the roof deck that offers a ringside seat straight up into the Acropolis. It is Sailor Boy’s birthday. We order moussaka, Greek salad, and ouzo. The salad is crisp and fresh, the moussaka piping hot, the ouzo strong.

Candles are lit on the tables. Beneath us, cats yowl and race over the rusted ruins of abandoned buildings. A musician plucks a bouzouki, his voice rising up into the twilight. The sky turns pink, and the Acropolis glows like an alabaster palace. As we finish the meal, the waitress brings a chocolate mousse topped with one glowing candle. I sing Happy Birthday. A few diners join in; everyone claps.

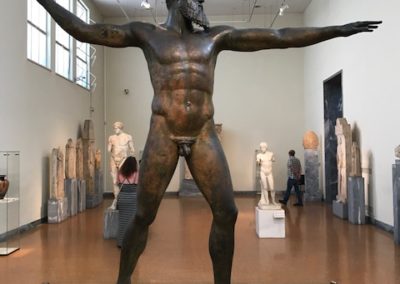

In the days that follow we climb the steps up to the Acropolis in the blinding sun and roam the grounds. We eat in cafes, stroll through neighborhoods, window shop. On the edge of the Agora, a restaurant owner and his son who have befriended us, pull out an extra table for our dinner while an opera singer enthralls the paying crowd below. We meet the new face of Greece, a young man who studied shipbuilding in Syros, a destination on our island stops. George returned to Athens when the Crisis hit, and joined his father’s taxi business. He glows with health and purpose, and insists on taking us to the National Archeological Museum and to see the changing of the guards at the Parliament. He becomes our informal guide and the one we turn to for his understanding of the country he loves.

At the National Archeological Museum, we wander star struck through the exhibitions for hours. Finally I step into an installation, Odyssey, awash in watery cobalt blues and the brilliant whites of marble statuary and artifacts. The exhibition illustrates the account of man’s journey through time, the homecoming of Odysseus, and the exodus. The poem “Ithaka” is recited in a continuous loop while the music of Vangelis silvers the air. I listen. Then I listen again. Here I find the unwavering voice of the people of Athens. They caution not to hurry the journey. What will I find, what will I hear on Crete, Paros, and Syros? We shall see. The blue Aegean is calling.

Ithaka

BY C. P. CAVAFY

TRANSLATED BY EDMUND KEELEY

As you set out for Ithaka

hope your road is a long one,

full of adventure, full of discovery.

Laistrygonians, Cyclops,

angry Poseidon—don’t be afraid of them:

you’ll never find things like that on your way

as long as you keep your thoughts raised high,

as long as a rare excitement

stirs your spirit and your body.

Laistrygonians, Cyclops,

wild Poseidon—you won’t encounter them

unless you bring them along inside your soul,

unless your soul sets them up in front of you.

Hope your road is a long one.

May there be many summer mornings when,

with what pleasure, what joy,

you enter harbors you’re seeing for the first time;

may you stop at Phoenician trading stations

to buy fine things,

mother of pearl and coral, amber and ebony,

sensual perfume of every kind—

as many sensual perfumes as you can;

and may you visit many Egyptian cities

to learn and go on learning from their scholars.

Keep Ithaka always in your mind.

Arriving there is what you’re destined for.

But don’t hurry the journey at all.

Better if it lasts for years,

so you’re old by the time you reach the island,

wealthy with all you’ve gained on the way,

not expecting Ithaka to make you rich.

Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey.

Without her you wouldn’t have set out.

She has nothing left to give you now.

And if you find her poor, Ithaka won’t have fooled you.

Wise as you will have become, so full of experience,

you’ll have understood by then what these Ithakas mean.